The Making of: Emotional Intelligence

We recently finished filming our new three-part video series on Emotional Intelligence with author Daniel Goleman. That's me in the center directing a scene from the movie. Erica DeLucia is standing to the right. For the last day of shooting we went to Dan Goleman's house in Massachusetts to create the "on-camera-narrator" scenes that glue together the various sections of the show. The article below is about the making of the films and particularly that last day of shooting with Dan Goleman.

I first met Dan at a wellness retreat back in the late 1980's. At the time, he was a science writer for the NY Times, and I asked him to narrate one of our relaxation videos. For some reason we never got around to doing it. But thirty years later, we met again at Kripalu Yoga Center in Stockbridge, Mass. where he and his wife Tara were putting on a seminar. We got to talking afterwards and one thing led to another and eventually we decided to create a series of training films that combined stress management, emotional intelligence and optimal performance.

A week before we actually shot the "on-camera" scenes in Dan's studio, I went up to scout it out. This is Dan standing near a big window and a bank of mirrors.(Both of which create problems for film-makers) There would be a lot to do to transform this small yoga studio into a "movie studio."

This is Dan standing in almost the exact same place as the above photo but after we "dressed the set."At this point we had hung a large felt backdrop, blacked out all the windows and set up at least five different lights. We weren't quite done with the lighting when I took this picture. You can see the left side of Dan's face is too "hot".

I really liked how his book, Emotional Intelligence, explains stress in terms of what happens in the brain. I felt like that approach would be very appealing to our clientele of corporations, hospitals and government agencies. It made perfect sense to me that the emotional brain, as Dan likes to say, hijacks the thinking brain, and that the thinking brain is powerless to stop it.

That little bit of brain science helped me understand why cognitive restructuring (see my recent blog) doesn't always work. And that was an epiphany for me. I'd spent years reading and absorbing the works of Albert Ellis and Aaron Beck, the founders of cognitive therapy. And even though Beck and Ellis both "promised" me (in their writing) that I could "stubbornly refuse to make myself miserable about anything - yes anything" (that's an actual book title of Ellis's) I found that there were many times, that no matter how hard I tried, I just couldn't do this.

But Dan Goleman (and his book Emotional Intelligence) comes along and helps me understand why I couldn't do what these renowned experts in the field of cognitive therapy were telling me that I OUGHT to be able to do. All my knowledge of cognitive restructuring - which resides in my thinking brain - does me no good at all, if my thinking brain has been hijacked by my emotional brain. In other words, there's no way I can "keep people from pushing my buttons" (another Ellis book title) if my thinking brain is taken off-line by the emotional brain.

And that's exactly what happens to us when we get caught up in a stressful event. By design, our emotional brain interprets the event before the thinking brain. By the time the thinking brain gets the information and starts to process it, the hijacking may already be well under way. And once your bloodstream is flooded with stress chemicals it's very hard to apply a creative and/or elegant solution to the problem because your ability to think clearly has been severely limited.

Your working memory, the area of your brain that holds up to seven or eight bits of information at any given moment (that might be useful to solving the problem that's making you so stressed) is also hijacked by the emotional brain which allows it to hold only the information it deems pertinent to the "crisis." By the time your thinking brain wrangles back control, the damage has already been done: You've already hit send on an email you'll later regret, or yelled at someone who didn't deserve it. And it may take up to 40 minutes for your body to flush out all the stress chemicals that have been dumped into your bloodstream.

Oftentimes, the emotional brain is flat out wrong, or over-reacts to the "perceived" threat. If you've ever woken up in the middle of the night to the sound of a loud crash coming from inside your home, only to discover it was the cat knocking something over, then you understand how wrong the emotional brain can be, and yet how powerless we are to stop it.

Dan and I met several times in New York City and up in Massachusetts trying to figure out how to put these great teaching points into a training video that would be both entertaining and informative. After seeing a copy of my film Recognizing Stress, Dan gave me the green light to use actors and "real life scenarios" to illustrate what was being said in the book.

I did most of my script-writing over the summer. One morning, I got the idea to have the characters in the film talk directly into the camera as a way of revealing their true feelings while they were simultaneously attempting to cover them up with the other actors in the scene. It's a common convention: when one actor looks into the camera, audiences understand that the other actor doesn't hear what the first actor is saying, because he or she is saying it directly to the audience. It's a cool trick, because it helps you (the audience) understand what's on the mind of the actor (in this case: their true feelings) while keeping these thoughts and feelings hidden from the other actors in the scene.

Part of emotional intelligence is about reading emotions in other people's eyes. We flash this shot (the one in the camera man's monitor) on the screen for just half a second and most people can tell the emotion is mild anger.

This was the idea I needed to help move me through the script-writing process. After I'd whittled down everything I'd written to three tight scripts I sent them off to Dan for approval. The next step was to arrange a casting session in New York. This is a part of the job I really love. There are a lot of talented actors in New York City. And we usually have fun working with a casting agency to find the best actors and actresses. For the casting call we decided to let everyone read the scenes that I wrote where the actors talk directly into the camera.

It's kind of amazing to conceive of a scene in your head, and then see how it plays out in the hands of talented actors (who always enhance it). When the people trying out (especially some of the better ones) began to look into the camera to reveal their inner thoughts, I knew we had something special...and something very funny. We couldn't help but laugh - even after people had repeated the same lines over and over. When I was writing it, I hoped the scene was going to be funny, but I had no idea how funny until I saw it acted out in person.

Once we had the cast in place, the crew hired and the locations nailed down Erica (my office manager/production manager) put together a "shooting schedule" and we shot all three films in five days. (Each of the three films is roughly 15 minutes long.) We worked long days but we had a great time doing it. Actors are so much fun to work with. (See the video blog.)

Two of the actors who survived the audition process in one of their scenes.

Then we edited the footage together using the script for guidance just like you'd use the picture on the box of jigsaw puzzle to get all the pieces in the right place: You have dozens of little scenes and hundreds of shots to cover those scenes including some in close up and some in wide shot. There were so many good takes it was difficult to decide which ones to use for each scene. After about a month of editing we sent the "rough cut" off to Dan for his final approval. The tension was high while we all awaited his response.

I'll never forget what he said when he called me back a few days later: "You know, a picture really is worth a thousand words, isn't it." I thought that was a great compliment coming from a writer who knew the value of a word.

Erica packing up some of the last things from the shoot in Dan Goleman's studio.

As we were packing up and putting the equipment away after our afternoon of shooting at Dan's place, I couldn't help but reflect on the year it took to create these films start to finish. Thinking about our first meeting, and our subsequent meetings and all the hours spent writing, editing and actually shooting the three films. It's always a bit emotional when you finally shoot the last scene in a film you've worked on for so long and so hard. And the experience of making a film is always very intimate, because you really bond with people even if you only spend one day with them. And it was easy to bond with Dan. He's a great guy.

In fact, to some extent, we were living out exactly what Dan talks about in his book, Social Intelligence (which also influenced much of the content in our three-part video series). In Social Intelligence, Dan points out, that when we build rapport with another person we actually sync up brain to brain. Our mirror neurons cause us to feel what another person is feeling. And that emotions, both good and bad, are passed from person to person, much like the common cold.

And all during the shoot, we were all connecting in a deep way, right out of the pages of Dan's books and you could experience the feel good chemicals being released in your head during every day of the production. There was so much laughter, so much interaction and a strong sense of camaraderie. So I felt a sense of not wanting it to be over, even the whole process was indeed coming to a close.

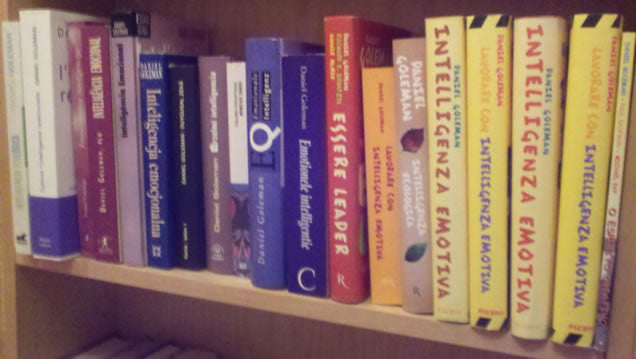

Other versions of "Emotional Intelligence."

As I was looking around to see that everything In Dan's studio was put back in place, I noticed a set of bookshelves, near the stairs going up to Dan's office. Each book was a variation on the title Emotional Intelligence. At first I didn't understand why there were so many slightly different versions of the same book. And then it dawned on me that these were all the different translations of Emotional Intelligence that had been published around the world. I'm not sure how many there were but there were a lot - maybe 30. And it helped me to realize that we had spent a very special day with a very special person who had brought a very special idea called emotional intelligence, to the whole world.

And now we were bringing out a new translation of the book, on film.

Also in Emotional Intelligence

Using Emotional Intelligence to reduce employee turnover By Lynn Thomas, JD

EQ is a key trait that employers should be looking for in employees in 2020.

Emotional intelligence (EQ) is our ability to be aware of, control, and express our emotions as well as understanding the emotions of others. There are many advantages to developing your emotional intelligence (EQ), but the most compelling is it is responsible for much of the success you achieve in life, much more than IQ! Also, unlike IQ, you can easily increase your EQ.

James Porter

Author