Stress, Perception and Getting long-Covid. Part 5

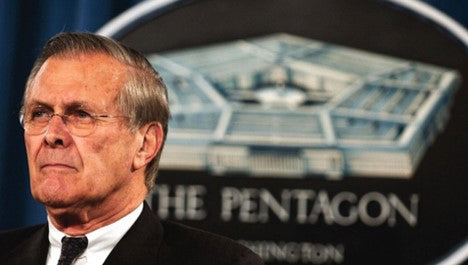

Former defense secretary, Donald Rumsfeld famously said: “There are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say, we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns – the ones we don’t know we don’t know.

The central theme of this six-part series has been about why so much of what we perceive is colored by misinformation or just flat out wrong. Most people don’t realize this. In other words, what former Defense Secretary, Donald Rumsfeld would call an unknown unknown. This series was inspired by the fact that after two rounds of covid I have been experiencing the world lately through the distorted lens of diminished sense (and sometimes total lack of) taste and smell. I know this.

Yet I am absolutely amazed how often I forget I can’t smell or taste things. As a result, I have incorrectly concluded that: The basil plant in my vegetable garden was NOT basil because it didn’t smell; A dead carcass in the road that looked like a skunk was NOT a skunk because it didn’t smell; My old, wet sneakers DIDN’T smell when they actually did. In other words, I KNEW that I couldn’t smell anything, but I still forgot – moving my lack of olfactory ability back into the territory of an unknown unknown.

These perceptual hiccups allowed me to see, firsthand, just how poorly the brain “sees” and how quickly it can turn even the lack of information into information. This was the thing that surprised me most. In all the examples above I turned the LACK of smell into information about my environment, all of which was entirely WRONG. Even without it being Covid-caused, we still perform this trick way more often than we realize. To illustrate my point, I wrote about confirmation bias in part 3 of this series where we tend to only see what we already believe (which totally explains how two people can completely disagree about what happened on January 6, 2020).

I also wrote about negativity bias in part 4, which explains why we often jump to negative conclusions: When we see a curvy stick in the leaves, we’re literally programmed to assume it’s a snake. In this situation it’s better to be safe than sorry. But in lots of other situations, it causes us to see the worst-possible scenario way more often than is truly necessary or helpful.

Daniel Kahneman, author of the best-selling book, THINKING FAST AND SLOW, described two parts of the brain that help us to better understand how and why we make these errors of judgment. He calls them: System 1 and System 2. They essentially separate “what we know we know” from “what we don’t know we know.” System 1 is consciousness. It’s what we know we know. System 2 is the unconscious part of the brain. It’s what we don’t know we know.

Negativity bias starts in a System 2 part of the brain called the amygdala. It was brain scientist Dr. Joseph LeDoux, who first determined that the amygdala was the originator of the stress response. LeDoux revised his thinking on the amygdala years later, possibly as the result of Kahneman’s brilliant work. He ultimately concluded that the amygdala was simply a threat detector. It’s the pre-frontal cortex or PFC, a System 1 part of the brain, he said, that takes the signal and decides what to make of it. In terms of our seeing things accurately the PFC can help straighten out a misperception born from negativity bias.

Where the amygdala just ASSUMES a curvy stick is a snake, the PFC takes a reasoned approach. It considers probability, sees the thing in the grass is not moving, and makes the correct determination: It’s a stick. The PFC, sometimes referred to as the executive center of the brain, also responds well to training. We can teach it to be on the lookout for these all-too-common misperceptions I have been writing about in this series. You have already begun this training process by simply reading this article.

It’s much easier to lay down new neural pathways which may result in new behaviors in the PFC (System 1) than it is to do it in the lower System 2 parts of the brain that are less malleable, or plastic. According to Kahneman, we use System 1 to train System 2. This radical, game-changer of an idea, often referred to as neuroplasticity, is often summed up like this: The brain changes in response to experience, throughout our lifetime.

We can use this ability to change our behavior and how we see things. Think of this like laying down a new path through an area of tall grass in your own back yard. You’d have to walk this same path, many times before it would become permanent. But if you are willing to make that commitment, you can make behavioral changes and observational adjustments that help you see the world more accurately and function within it better. Your new pathway might be designed to help you reduce worrying or to help you keep from losing your temper, or to help you take in new information contradictory to what you THINK YOU KNOW.

Secretary Rumsfeld accurately pointed out that the most dangerous configuration of all the knowns is the unknown unknowns. NOT knowing what we DON’T know and need to know will get us into trouble every time. And dispelling the notion that the information YOUR System 2 part of the brain is delivering to System 1 is always accurate is what this blog series has been all about. And until this moment, that may have been a CLASSIC example of what you didn’t know you didn’t know.

In my final installment, I’ll write about how my diminished sense of taste and smell evolved into a DISTORTED sense of taste and smell where much of what I encounter tastes and smells the same. (And trust me, it’s not a pleasant taste or smell.) Covid has literally left me with a bad taste in my mouth. But when I described this exact situation to my daughter, she rebranded it as a SUPERPOWER! I’ll explain why in the next installment.

James Porter

Author